Thinkers committed

to transformative practice are likely to exhibit

at least as peculiar 'forms of life' as found in any of the later Wittgenstein's

'language games'.

Nietzsche's as well as

Steiner's practices foreshadow the movement of thinking in

our

era to uncover Time as thinking's proper element. And because their

practices bring time together in life, and because

life

realizes time with evidence that makes thought pale, we must

interpret these two on the basis of their lives and not only what

we find in the pictures they offer.

Thinkers committed

to transformative practice are likely to exhibit

at least as peculiar 'forms of life' as found in any of the later Wittgenstein's

'language games'.

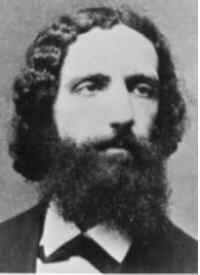

Nietzsche's as well as

Steiner's practices foreshadow the movement of thinking in

our

era to uncover Time as thinking's proper element. And because their

practices bring time together in life, and because

life

realizes time with evidence that makes thought pale, we must

interpret these two on the basis of their lives and not only what

we find in the pictures they offer.

VI(c) |

|

New

foundations for meaning: myth

uncovers metaphor as meaning's deepest roots and as the basis of

thinking's openness to the past. Religion's way of

conjoining presence, future and past as opennesses.

|

Thinkers committed

to transformative practice are likely to exhibit

at least as peculiar 'forms of life' as found in any of the later Wittgenstein's

'language games'.

Nietzsche's as well as

Steiner's practices foreshadow the movement of thinking in

our

era to uncover Time as thinking's proper element. And because their

practices bring time together in life, and because

life

realizes time with evidence that makes thought pale, we must

interpret these two on the basis of their lives and not only what

we find in the pictures they offer. Thinkers committed

to transformative practice are likely to exhibit

at least as peculiar 'forms of life' as found in any of the later Wittgenstein's

'language games'.

Nietzsche's as well as

Steiner's practices foreshadow the movement of thinking in

our

era to uncover Time as thinking's proper element. And because their

practices bring time together in life, and because

life

realizes time with evidence that makes thought pale, we must

interpret these two on the basis of their lives and not only what

we find in the pictures they offer. |

|

Though

Nietzsche tilted at the windmill of the future, his knightly

armour sparkled and creaked with his own time's apparatus of the

sciences, even while a great deal of his challenge unfurled to

pointedly mock the history of 'civilized institutions'.

|

|

The

Anti-Christ

titles one of Nietzsche's later works. |

Madame Blavatsky and Anne Besant were chief Theosophists, the movement in which Steiner found followers and from which he broke away. |

|

Steiner

never admitted that suicidal narrowing into national identity as

his land's fate accompli; he found sufficient diversity and

aptitude for what he tried to teach as 'supersensible perception'

among the people who sought him out, to dedicate his life to them.

Steiner made use of the cultural potencies at hand to give his

practice social effect. So unless we can begin to recognize the

scope of Steiner's intentions, the means he brought to bear might

make his work seem nearly antithetical to the advance of thinking,

might even suggest that he was involved in a confused (and

confusing) conglomeration of atavisms.

|

| Steiner's

The

Education of the Child is

one place to learn more. Also the beautiful Education

Toward

Freedom, text: Frans Carlgren. layout: Arne

Klingborg,

Lanthorn Press. And recently, the delightful Natural

Childhood,

John

Thomson, ed., Simon and Schuster |

As a 'renegade', a thinker

involved in

transformative practice,

Steiner leaves us no culminating type of synthesis which can

picture us the order and value of his thought, though anyone who

observes a healthy Waldorf school might have from Steiner something

better than such a picture. Here is one way Steiner has sent

himself toward the future - through the children as a favor to

them. One wonders what it says about our time that such a result of

thinking could remain so little acknowledged for so long.

|

|

The amorphousness of Steiner's

legacy is compounded not only by the

instrumentalities of its dissemination in his time and additionally

its mediations in our own, but also by the nature of the direction

in which he was fundamentally turned. Steiner surely stood at the

other end of the boat from

Whitehead and

Nietzsche as it crossed into the twentieth century, looking

not

toward the unknown land looming in advance but into the homeland

vanishing aft.

|

|

Steiner's work, like Dilthey's and Husserl's in its prodigiality, embodies a response to the Romantic position that Mind's foundations and its capacity for truth belong first to Mind's productivity - to use Goethe's word in Faust, its deeds.  |

Steiner's six-thousand-odd

transcribed lectures are mostly staged on the basis of what most

thinkers would take as mythological content, and within those

lectures Steiner works to call forth apprehensions whose meanings

employ such 'mythic' frames of reference. Even by late

nineteenth century standards, when the study of myth seemed to be

of preeminent importance for coming to terms with the origins and

destiny of humanity, Steiner's approach constituted the breaking of

taboos for many of the thinkers of his time. Not just because he

could be seen as the focus of a 'cult', but even more because

instead of using myth as a subject for conceptual analysis, he

asked for a kind of participation in typically mythic distinctions

which could not be reduced to objectifying relations: Steiner said that he meant to teach Imagination,

Inspiration, and Intuition. These words

signified

faculties offering insights and relations in reality which were not

susceptible to capture in externalizable ideas. Their truth was

characterized as a function of the concrete reality whose gathering

together constituted their occasion. Such truths belong to their

moments as incarnations for awareness and can not be well used as

building blocks for systems of concepts.

|

|

|

But how is it

this

lives in

thy mind?

What seest thou else in the dark backward and abyss of time? |